The Rise and Fall of Processed Tomato in Taiwan

The sixth instalment in our project blog, where From Collection to Cultivation members share research insights, snippets, and ideas.

When mentioning my research on the tomato breeding program of the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC, today known as the World Vegetable Center), a usual response I receive in Taiwan is “but aren’t tomatoes a fruit?” As the consumption of raw vegetables in Taiwan remains a novel practice associated with the Euro-American diet, tomatoes might be considered vegetables only when cooked, as in tomato-and-egg stir-fry or tomato-beef noodle soup. Aside from these dishes, people in Taiwan encounter tomatoes more commonly as a fresh fruit. My first memory of tomatoes is thus not the large, round, and bright red tomatoes that are cooked as a vegetable, but the small, oval-shaped, and slightly orange cherry tomatoes in school lunch. To be honest, I never really enjoyed fruits in school as a kid and secretly held the desire to indulge in nearby fast food chains where tomatoes are reduced to ketchup and paste—such an irony considering the “ketchup as a vegetable” controversy in the United States, resulting from budget cuts for school meals.

The puzzle about the relative popularity of fresh versus processed tomatoes in Taiwan concerns not only culinary preferences but also agricultural and food policies. The rise and fall of the country’s processed tomato industry, which traces its roots back to the colonial era and reached its zenith in the 1970s and 80s, testifies to this. After the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Taiwan, an island inhabited by Austronesian Indigenous peoples and Chinese settlers who arrived in the seventeenth century, became a Japanese colony. By the 1920s, the colonial government had incorporated settler farmers into the rice and sugar production system of the empire. Southern Taiwan was especially valued as a frontier for tropical agriculture, and tomato varieties from the United States such as Ponderosa and Marglobe were introduced in the 1930s.

Following the end of the World War II, the Republic of China (ROC) took over Taiwan with the support of the Allied Powers. Nevertheless, the relocation of the ROC government to Taiwan after its defeat in the Chinese civil war with the Communist Party put the island on the frontline of Cold War geopolitics. To enhance the legitimacy of the ROC, an agency called the Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction (JCRR) was financed by the US government to inherit and expand the agricultural project left by the Japanese. During the 1950s, the JCRR implemented a series of land reforms to turn tenant farmers into landowners of rural co-operatives. It also continued to increase rice productivity by improving irrigation and access to agrochemicals. The combined effects prompted farmers to diversify from rice and invest in cash crops like pineapples, asparagus, and mushrooms. These crops were chosen by the JCRR to facilitate the growth of agri-businesses, in particular canning factories that would produce goods for the export market.

While the JCRR was instrumental in resuming the introduction of tomato varieties from the US, the canning factories led in the development of the processed tomato industry. By the 1960s, factory owners began to encourage the cultivation of tomatoes, a winter crop, to fill the gap before the harvest of asparagus in the spring and pineapples in the summer. In 1967, Kagome, the largest supplier of processed tomato products in Japan, decided to establish a plant in Southern Taiwan to produce tomato paste, purée, and ketchup. Taiwanese agri-food companies quickly followed suit and forayed into the processed tomato business. Furthermore, as Taiwan embarked on rapid economic growth by 1970, urban demand for fresh tomatoes also skyrocketed.

Tomatoes consequently became one of the six crops chosen by the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC), an international research centre founded by JCRR scientists in 1971, coincidentally just a few miles away from the Kagome Company. One key priority of this centre was to breed tomatoes resistant to the heat and bacterial wilt that hampered summer tomato production. After screening thousands of germplasm entries across the globe, a team of Taiwanese and Filipino scientists began in 1979 to release tomato varieties specifically adapted to the tropical summer. However, changing Cold War politics during the 1970s—the ROC’s expulsion from the United Nations in 1971 and the end of diplomatic relationships with Southeast Asian countries in the mid-1970s—threatened to marginalize the AVRDC from regional research networks. Facing the crisis, the centre complemented the breeding of tomatoes intended for processing with research on varieties for fresh consumption that were enriched with vitamins A and C. Beginning in the 1980s, the AVRDC promoted the latter varieties in home gardening projects in Thailand and Bangladesh. These research programs then enabled the Center to retain its relevance by appealing to the growing emphasis among international development organizations on smallholders and nutrition fortification.

Unexpectedly, the lasting influence of the AVRDC in Taiwan was less the tomatoes bred for the food processing industry than the varieties destined for fresh consumption. By 1990, after three decades of urbanization and industrialization, high labor costs made processed tomatoes from Taiwan largely uncompetitive in the global market. The centre’s research on heat and disease resistance nonetheless contributed to the growing popularity of fresh tomatoes in the domestic market. It ultimately made tomato a common fruit comparable to banana and pineapple, affordable enough to become a recurrent item in my school lunch menu in the 2000s.

Learn more about Leo Chu's research on the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center and the history of agricultural development in Taiwan.

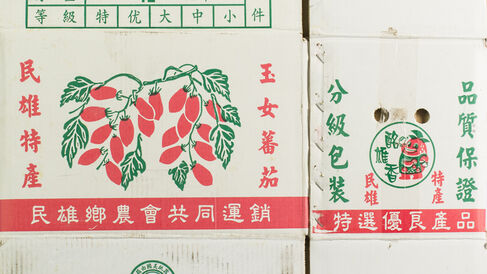

Image credit: Cardboard box for cherry tomatoes produced in Minxiong, Southern Taiwan, 2019. Photo by NGO Walking Grass Agriculture, licensed under CC-BY 3.0.